We are at the peak and crest of the wave of what we call Medical Evidence-Based Science, or at least the search for and understanding of it.

That's how research is done

We have to gather information from studies carried out by researchers at universities around the world and draw conclusions based on real evidence, not just opinions or individual experience. We have to be truthful and report what we do well and what we do badly and not be afraid to compare our results with those of our peers, with those who do the same as us, who occupy their time with the same type of scientific, medical, academic or surgical occupation.

What kind of professional do we want to be?

When we pursue a professional activity, we have to be able to define where we want to place ourselves: among those who carry out well-studied techniques that have been proven by reason and experience. Those who carry out techniques that are fantastic, that give them notoriety, but that only a handful of scientists can carry out perfectly. Those who study and try to improve their techniques on a daily basis. Those who research and create new techniques, building on existing knowledge and adding something new, based on scientific support.

Scientific Evidence vs Commercial Evidence

Scientific evidence is not always the same and is not aligned with commercial evidence. Commercial evidence is the evidence that works best for patients and that is not always aggregated as the best or most scientifically evident option. We are going through a desert in which there are fewer resources available and with this, the fight for survival leads to and legitimises everything; we are in the era of “anything goes”:

– An education system that churns out 750 graduates a year for an already saturated and exhausted market.

– Large groups treating everything and everyone like Excel sheets.

– Clinics advertising real miracles and almost unique techniques that often lack the mastery and control they should have over the medical and surgical process.

– The confusion that exists in which all dentists seem to know how to do the same thing and have studied the same thing, where some are able to learn and grasp in a weekend course what others have taken years of dedication, study and experience to do.

And where are the patients in all this confusion, how can they protect themselves?

Just as we doctors and researchers do when we are collecting scientific information, we have to know how to carry out a process of validating content and sources, in other words, we have to realise whether what is said in a scientific article is true, useful, reproducible and has reliable sources.

And we have search engines, we have appropriate places to do the “screening” to make sure that the new techniques or concepts that are being announced and introduced into the scientific or medical environment are serious and reproducible in an “in vivo” context, in our patients and not just in an “in vitro” environment, just working in the laboratory in an environment with exceptionally controlled external conditions and variables.

From this I would like to conclude and warn that the treatment process based on a serious, professional and honest doctor-patient relationship, like any other type of relationship, scientific or social, depends on the two observers, depends on the two players, in this case it depends on the doctor and the patient.

The relationship depends on the two parties involved

It should be a serious process of mutual and bilateral responsibility.

The doctor must be responsible for:

– Respecting the patient and maintaining a cordial and comfortable atmosphere with the patient undergoing treatment.

– Having the necessary qualifications to be able to carry out what he or she claims to be able to do.

– Guaranteeing the seriousness and quality of their sources, their bases, the places where they have learnt and gathered their knowledge.

– Protect the patient by selecting the best quality products and the most predictable and well-studied techniques.

– Do not experiment on patients, except in properly prepared studies, in research centres and after the respective ethics committees involved have given a positive opinion and “green light” to such experiments.

– You must inform the patient as much as you can and know about the treatment you are proposing, explaining the advantages, disadvantages, dangers, possible complications, duration and longevity and the respective guarantees.

The patient must be responsible for:

– Respecting the doctor and maintaining a cordial and comfortable atmosphere with the treating doctor.

– Gathering information about the doctor they choose to treat them and understanding and researching their qualifications and CV. We can’t run the risk of wanting to compare professionals, and sometimes it can even become offensive to compare different professionals, and even to compare fees for professionals who have nothing to do with each other in terms of experience, CV or the type of materials and facilities used in the treatment.

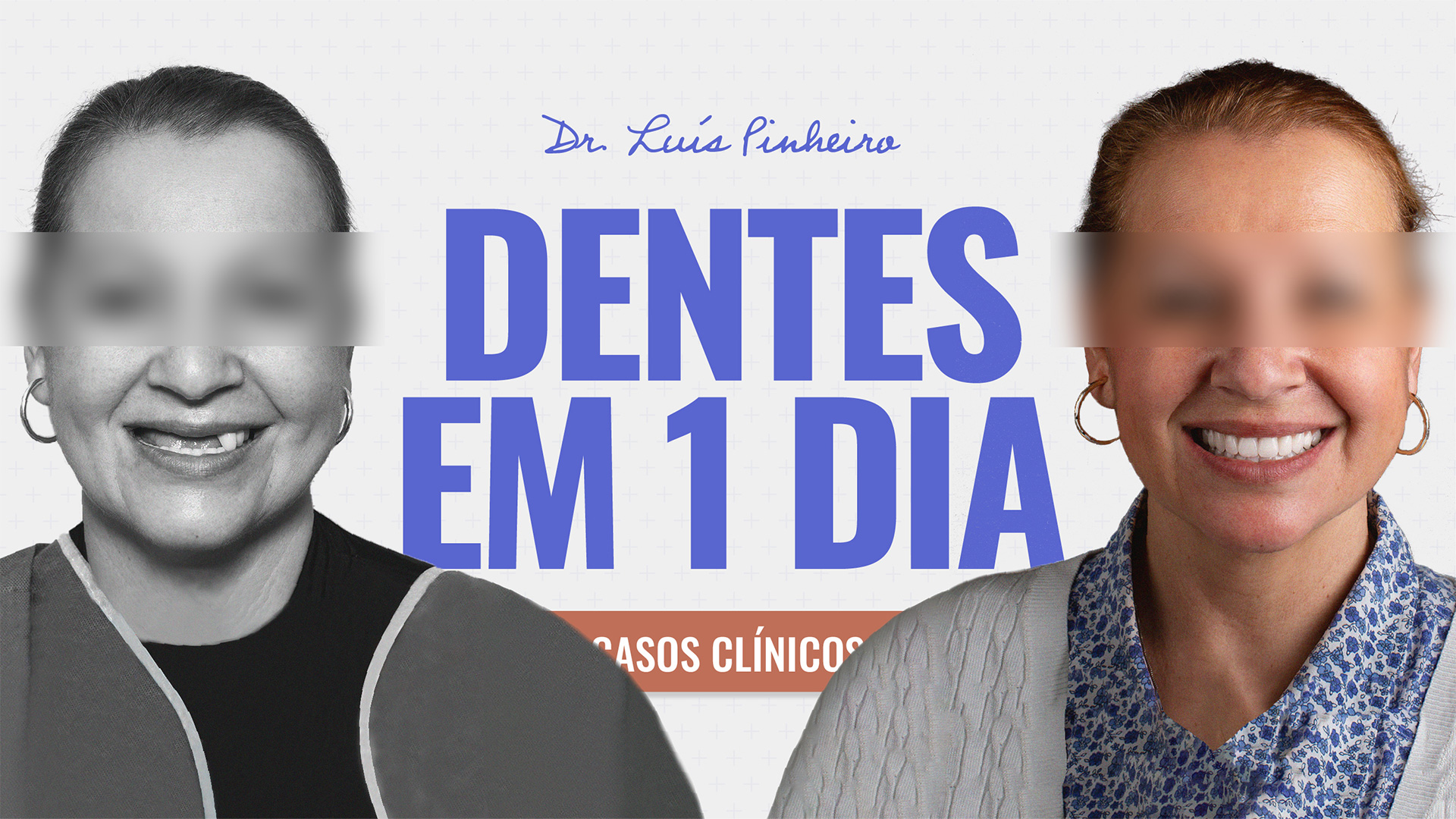

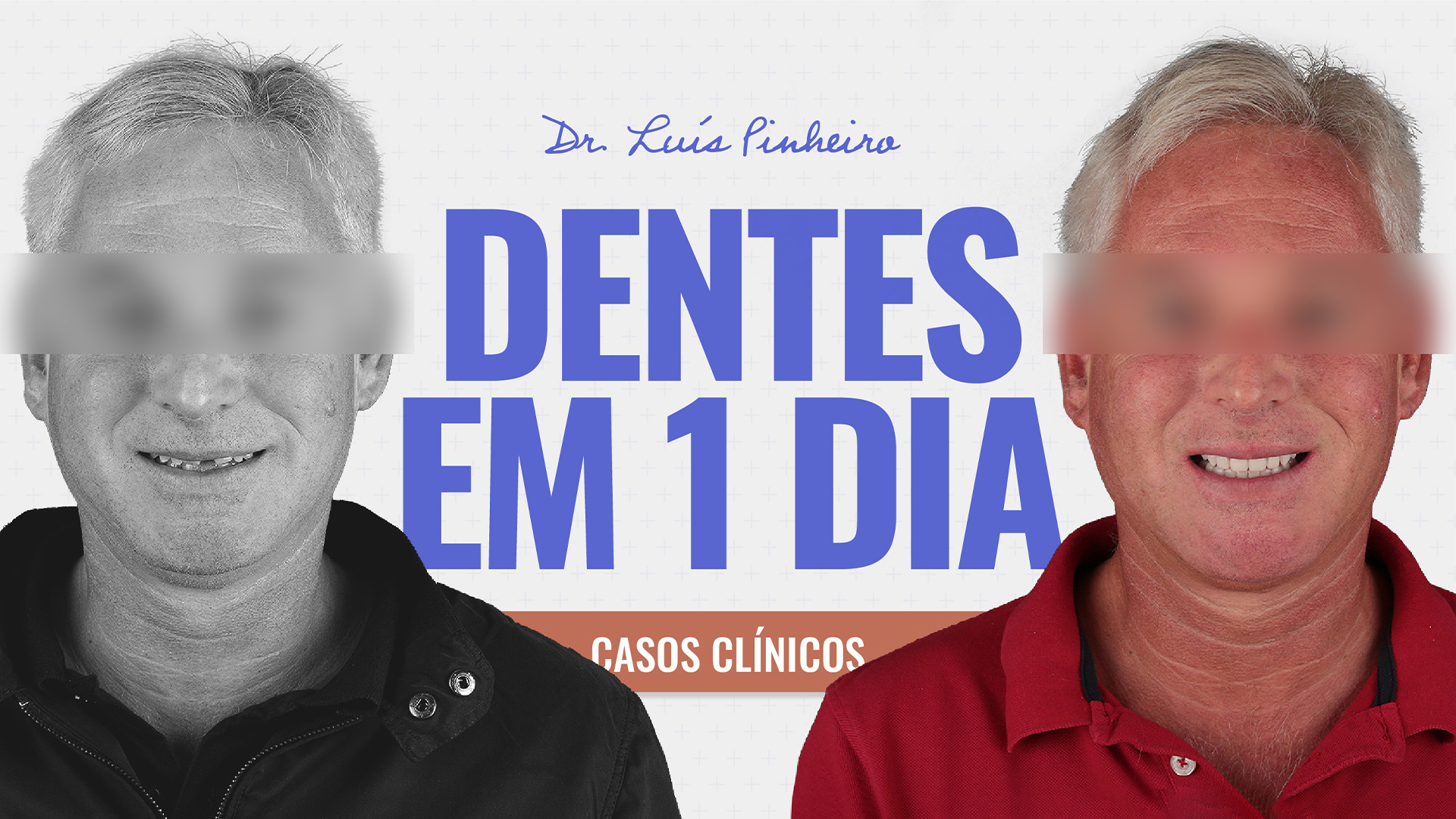

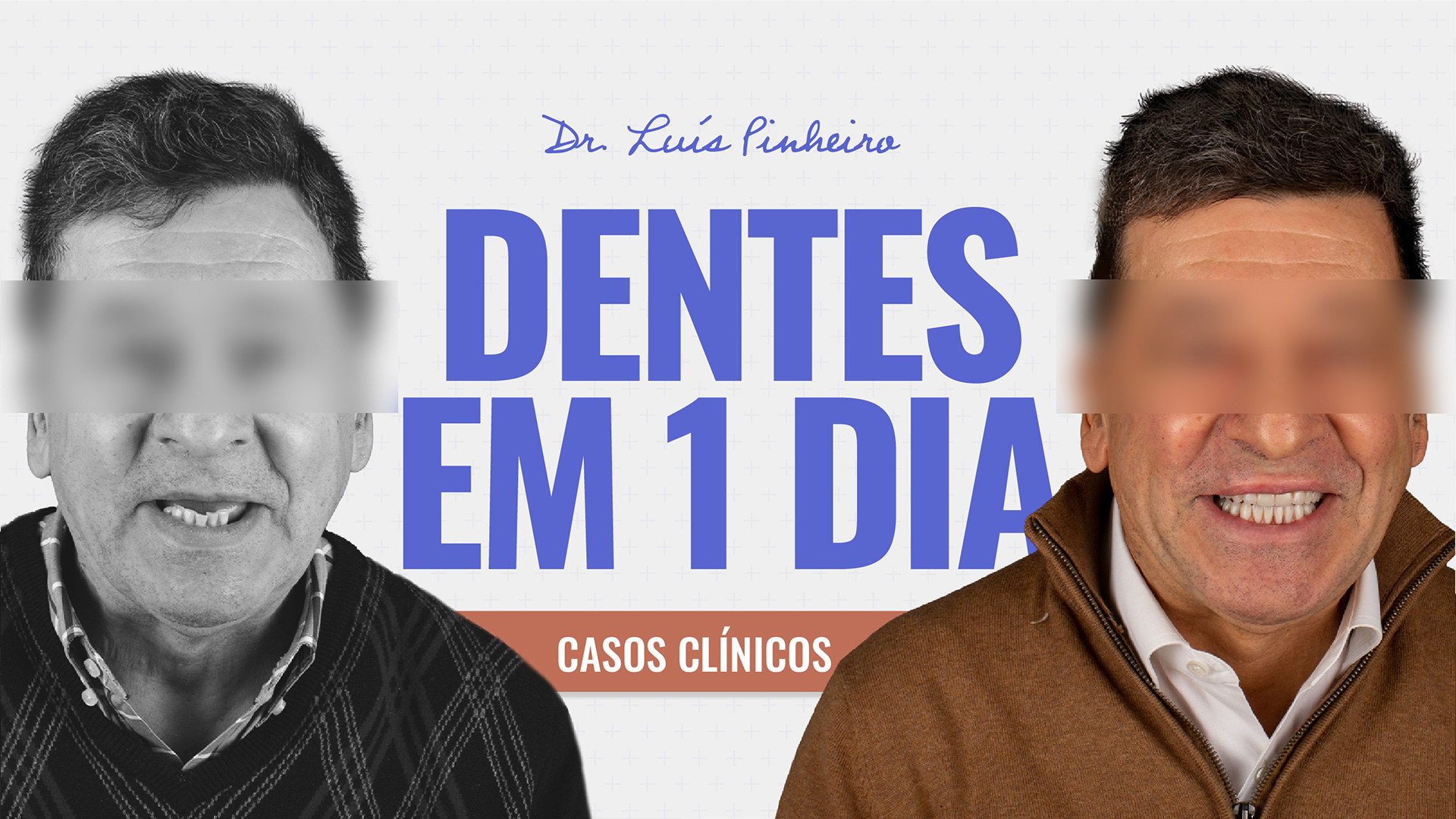

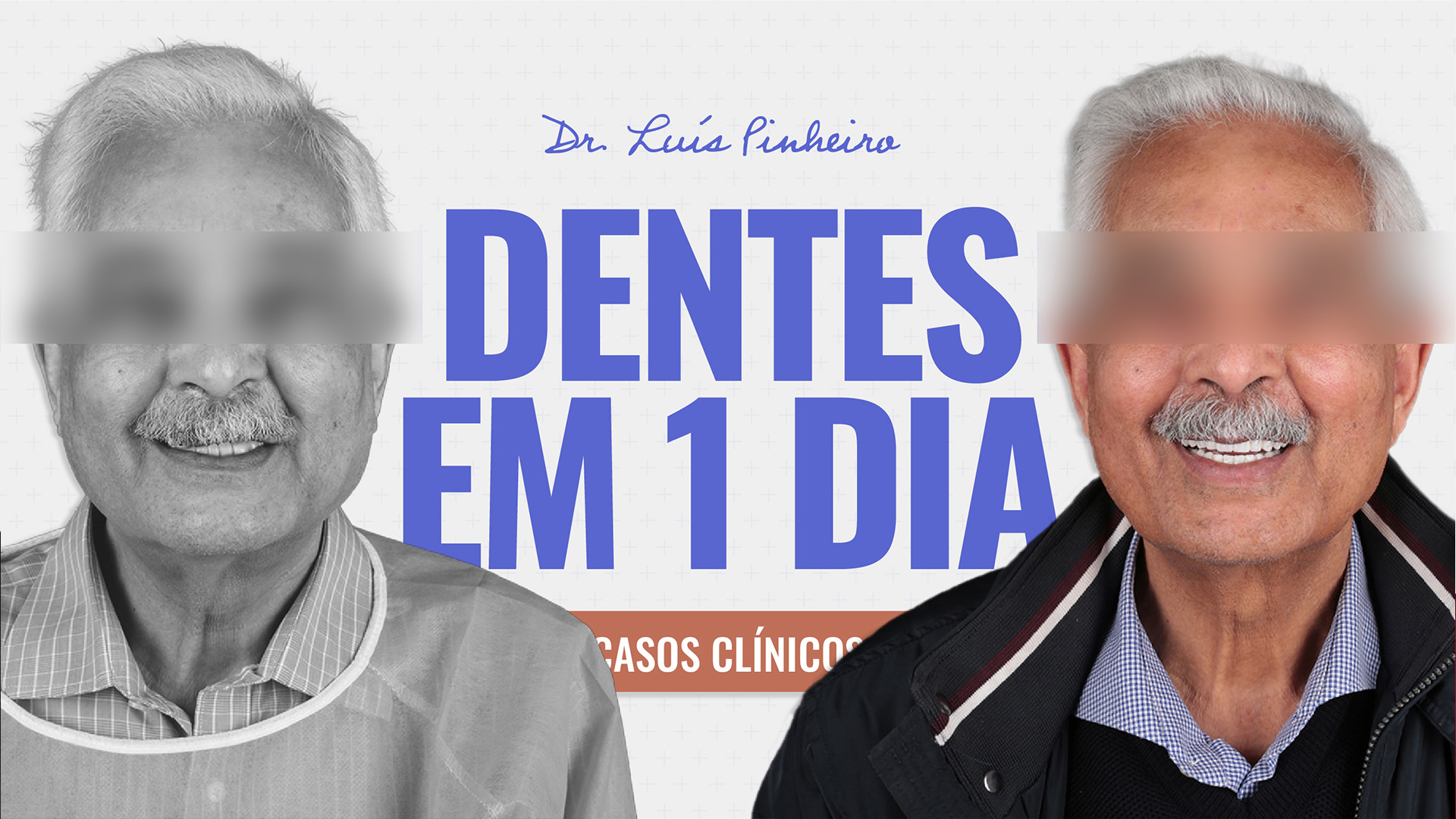

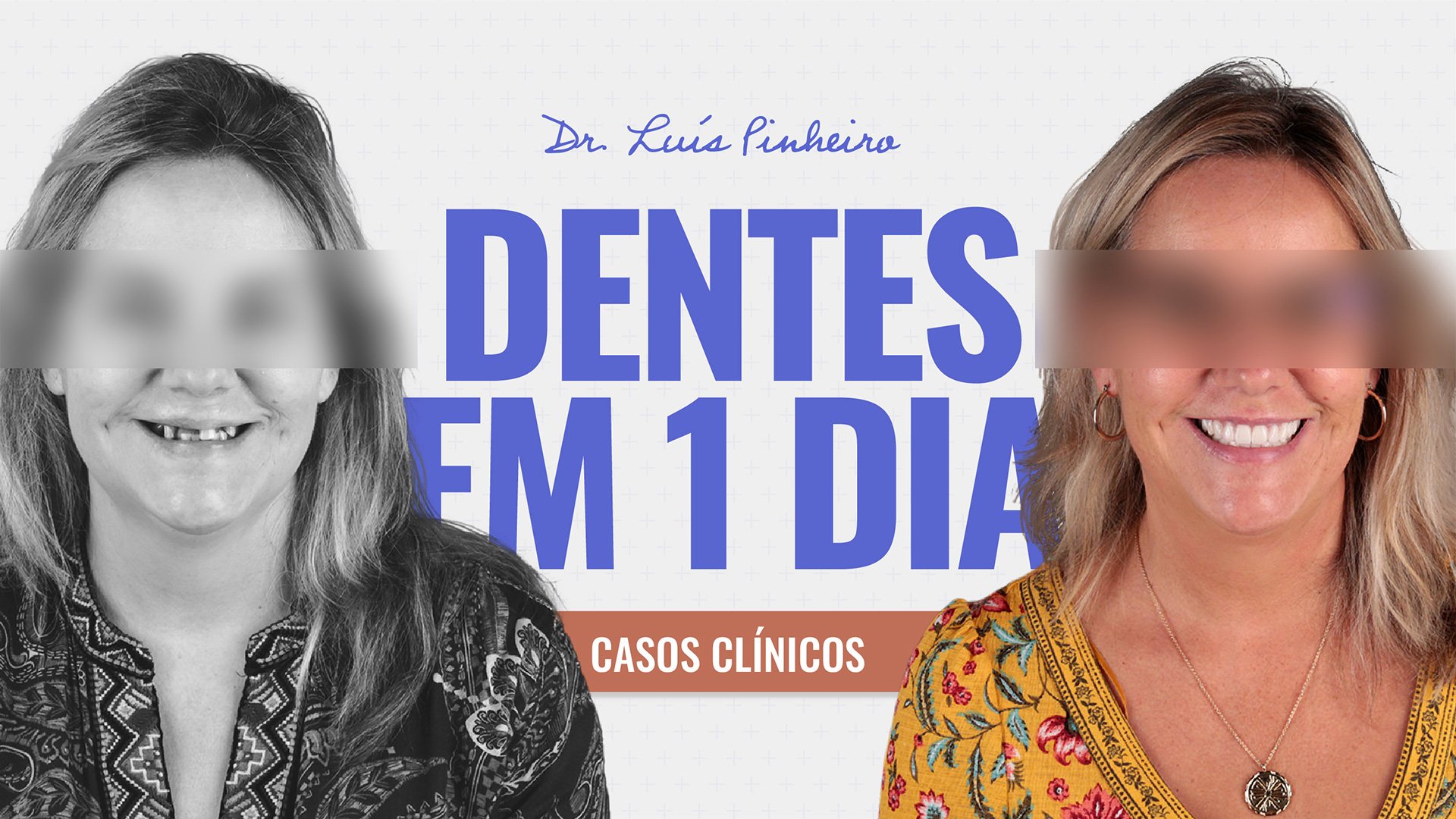

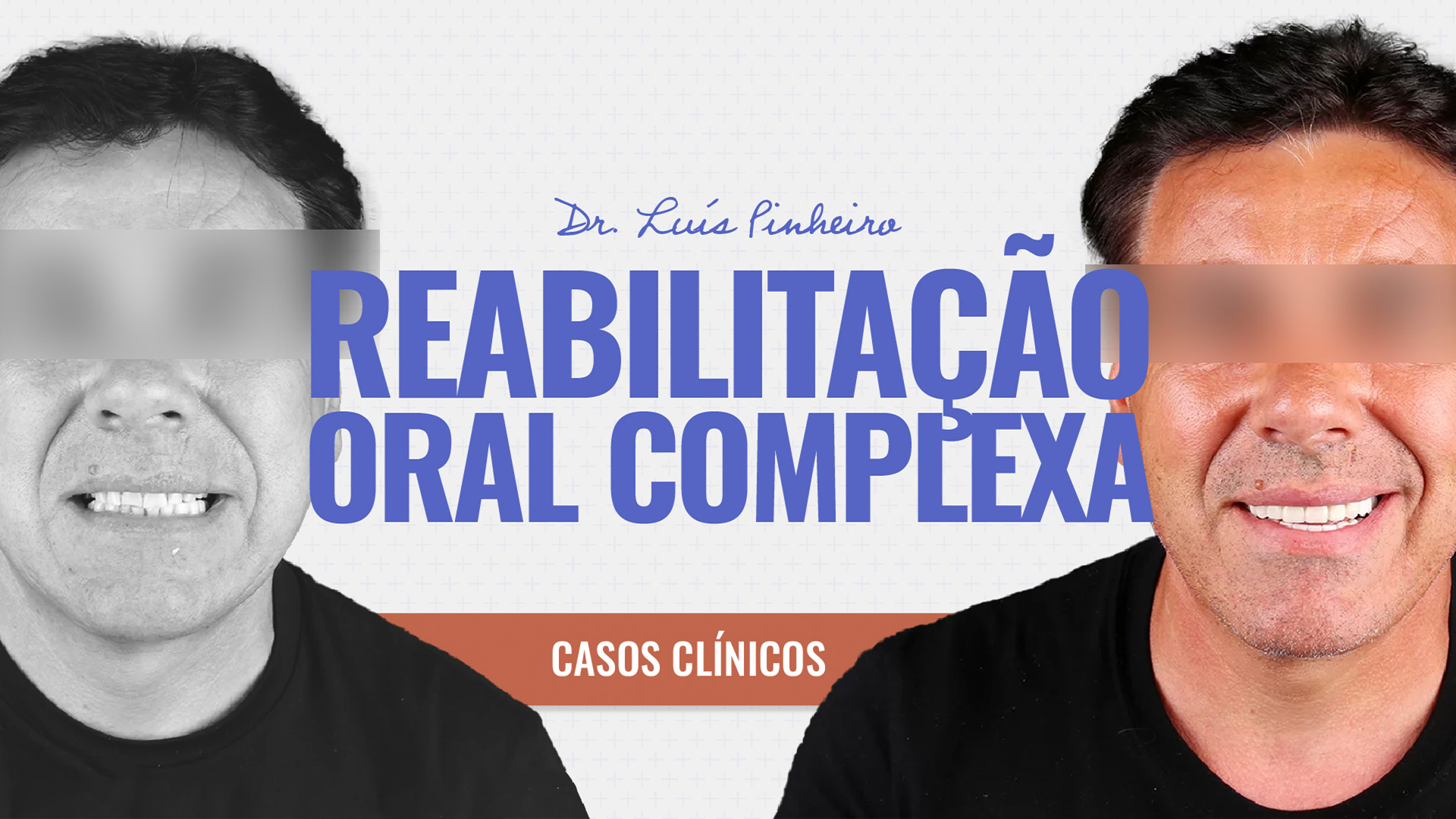

– Ask the doctor to show you similar Clinical Cases that have been treated, with images, photos and X-rays of situations that can be used during the patient’s treatment.

– If possible, collect information from patients who have already been treated using similar techniques, safeguarding the data protection of those involved.

– The patient himself can be informed of his treatment options so that he can play a more active and informed role with the doctor in order to share responsibility when deciding on the treatment plan.

Without illusions

We shouldn’t delude ourselves or be dishonest and say that everything always goes as smoothly as possible in all interventions and that we can guarantee 100 per cent fulfilment of patients’ expectations.

Expectations and their management, also bilateral

Expectations on the part of the doctor:

The doctor has to be able to manage their expectations in a clinical and scientific context that their techniques and knowledge at their disposal will be sufficient in all Clinical Cases to be able to treat the patient. However, this is not always the case and this is also why the professional is forced to:

– Look for new, well-studied and proven materials

– Consider sending the patient to a colleague who is better prepared and qualified to carry out the treatment

– Realise that it’s time to improve their curriculum and seek knowledge, study and train with more experienced doctors and surgeons.

– If you don’t want to study further, you must realise your limits and not exceed them, running the serious risk of not being able to carry out the treatment plan with the rigour and quality that you should, which could result in great harm to the patient.

Expectations on the part of the patient:

– You should realise that the impossible is the enemy of balance and common sense, and you should think about and measure your expectations of the treatment very carefully so as not to be disappointed.

– Ask the clinician for a precise, complete and very enlightening explanation and compare your expectations of the treatment and the possible end results.

– Understand all possible complications during treatment.

Maintain a good relationship

Like all relationships, whether professional, medical or personal, they depend on a very specific balance and dynamic that requires maintenance and effort on both sides.

With education, common sense and seriousness, science can be at the disposal of both the doctor and the patient in this fantastic process of restoring and improving the health, function and aesthetics of the human body

The seriousness of the whole process is based on the science of the relationship between doctor and patient.

I’ll end by thanking you for your time and attention.

See you soon and don’t forget to be happy. After all, smiling doesn’t hurt.

If it does, if smiling causes you pain, nausea or imbalance, consult your dentist.

Until next time!