This is a universal truth in medicine and other sciences that investigate and interpret signs and symptoms. For us clinicians, the signs and symptoms that the patient reports to us are clues that lead us in our medical, scientific and logical reasoning towards the guiding thread that will allow us to associate our knowledge accumulated over decades of study and crystallised by our medical and surgical practice over the years and long hours working with our patients.

On the other hand, our society is evolving exponentially, and scientific knowledge is now much easier to obtain and distribute throughout the world’s centres of knowledge at a speed that makes us feel small, slow and limited in keeping up with the best and most up-to-date developments in our field of interventional medicine.

Every day, scientific articles are published on a particular topic in a particular area and it is with these contributions, smaller or larger, that all added together, at the end of the day, they allow science to advance, they allow us doctors to keep up with that same advance and from this symbiotic relationship between doctors and science, where both contribute to mutual success, that at the end of the process, it will be the patients who will be the great winners, and the doctor-patient relationship, the one that we have learnt and do everything we can to ensure is correct, balanced, fair, perfect and protected, will be tremendously enriched.

With this enormous technical and scientific evolution, we have gained a new “armoury” in our daily clinical practice that allows us to be increasingly quicker to diagnose, more accurate in establishing a treatment plan according to priorities and severity, and more predictable and safe in the treatments we offer as an option to our patients.

And these treatments tend to be more predictable, effective and efficient. Why is that?

For:

- Having better means of diagnosis

- Working every day to enrich our training curriculum, from the medical, scientific, technical, radiological, IT and so on areas

- We can’t talk about surgery today, in my case Oral Surgery and Implantology, without talking about the digital and computer technology that helps us in surgery.

This technology is involved in:

- Diagnosis

- Planning

- Treatment

- Post-surgical control and maintenance.

When I see a patient for surgery, I start by taking a Medical History.

In my opinion, there is no medicine without a medical history.

In the same way that we, as individuals, are a result of our stories and our experiences, the patient with their symptoms and the signs that we observe in the careful examination of the patient, intra-oral and extra-oral, is also ready to tell their story.

We have to know how to listen to the patient. To listen to and understand the stories and histories, those that may have a practical and direct bearing on the pathophysiology of the disease and those that are only there to distract us, or at most to help the patient himself to remember and fit the pieces of his own puzzle together.

When it comes to diagnosis, it is essential to have access to the best and most up-to-date diagnostic aids, and this is something that the good practice of Oral Surgery and Implantology can never do without.

Here, in particular and very significantly, imaging takes on crucial importance in its radiological aspect.

I have up-to-date technology at my disposal in my clinics, "cutting-edge technology" as it is now so fashionable to refer to it.

1- Digital periapical X-ray with which we can detect and/or evaluate and measure:

- small hard tissue lesions in the area surrounding the tooth

- presence of dental caries

- Intra- and extra-radicular resorption

- Proximal and distal bone defects in relation to each tooth

- Distance to relevant anatomical structures, such as nerves and anatomical cavities that cannot be injured, let alone damaged, with temporary or definitive clinical manifestations and complications

- Intra- and post-operative positioning of dental implants

- Inflammatory and infectious bone diseases

- Dental trauma

As a limitation, and speaking in general terms, we have the size of the intraoral probe, which precisely because it enters the oral cavity, is of a reduced size and therefore the radiological image will also have reduced limits, not allowing us to assess more than 1 to 3 teeth and their surrounding areas with each dose of radiation.

2- Panoramic X-ray, Digital Orthopantomography, which offers us an important diagnostic aid in various situations:

As its common name describes, the panoramic X-ray, the so-called Panoramic image, offers the clinician who requests and studies it a general image of the hard tissues, bones and teeth of the oral cavity, nasal cavity and antral cavity (maxillary sinus), for example:

- It serves as a first diagnosis and a platform from which to start building a treatment plan.

- It allows us to visualise all the teeth in the mouth and their adjacent structures (periodontal ligament and alveolar bone) in just one 2D section (2 dimensions).

- In terms of trauma, we can detect a reasonable percentage of dental trauma (the first choice being a periapical x-ray), trauma to the jaws, mandibular bone and maxillary bone, trauma to the temporo-mandibular joint (not the first choice test for this type of diagnosis).

- Granulomatous and cystic hard tissue lesions

- Planning implant surgery

3 – C.B.C.T. (Cone Beam Computed Tomography), which offers a 3D study of anatomical structures and arose out of a need to have more reliable and accurate information than a 2D scan such as orthopantomography, but which could also emit less radiation than a conventional CT scan.

It allows:

- A more detailed and complete study for planning implant surgeries.

- A safer approach to tooth extractions near noble anatomical structures, such as nerves.

- Rigour in measuring present and available bone dimensions

- Virtual planning of surgeries with the possibility of placing implant models with the respective qualities and dimensions on the image

- 3D image reconstruction for oral and maxillofacial surgery

In my clinical practice, patient safety always comes first, whether it's accident prevention, biological contamination, so-called cross-infection between patients and medical staff and between patients, or radiological risk assessment and protection.

It all starts with the clinical history and the collection of information on the patient’s state of health. Whenever possible, we avoid the use of radiation, particularly in pregnant women and children, respecting the specific guidelines for the situation from both the Directorate-General for Health (DGS) and the Order of Dentists (O.M.D.).

Our clinics are built in accordance with the requirements, have protective equipment for patients and staff, radiation meters and tight radiological safety controls by the competent authorities and audited by independent bodies set up for this purpose.

As I believe that our patients are increasingly interested and active in sharing therapeutic decisions in the doctor-patient relationship, I would also like to add to this article a comparison of radiation between different radiological examinations.

The latest and greatest CBCT machines, such as the one we have in our clinic, allow pulsed light to be emitted instead of continuous light, which just to give you an idea:

– A scan lasts between 5 and 40 seconds, depending on the type of examination and the area to be registered. The larger the area, the longer the exposure time.

– For a 20-second scanner, we could have an exposure of 3.5 seconds to radiation alone with the emission of a pulsed light beam (Whaites E, 2013).

The effective dose of radiation depends on:

- Amount and time of exposure

- The size of the field of view, F.O.V. (the larger, the more radiation)

- The type of equipment used (modern digital equipment emits less radiation than older analogue equipment)

- The anatomical location of the field to be irradiated and studied (Whaites E, 2013)

Examples of Radiation levels according to the type of Radiological Examination:

(Effective dose units – (E) mSv)

- Periapical Radiography – 0.0003 – 0.022

- Panoramic Radiography – 0.0027 – 0.038

- Trunk X-ray – 0.014

- Skull X-Ray – 0.02

- Head Computerised Tomography – 1,4

- Tomography Abdomen – 5,6

- Jaw CT – 0.25 – 1.4

- CBCT dento-alveolar – 0,01 – 0,67

- Craniofacial CBCT – 0.03 – 1.1

(Whaites E, 2013)

As with everything in life, we have to know how to adapt and select the right diagnostic aid for each clinical situation.

There is no such thing as a perfect test and proof of this is the fact that sometimes we have to order and perform more than one. But nowadays, with the technology we have at our disposal, we contribute to an increasingly predictable, effective and safe clinical practice, and the possibility of being able to virtually plan our surgical interventions allows me as a surgeon to be increasingly secure, confident and happy with the technology that helps us in our daily work, both in my area of Oral Surgery and Implantology, and in the virtual planning of Oral Rehabilitation itself. But I only talk about what I know, and I leave it to my colleagues to talk about their specific areas.

This is the beauty and safety of teamwork, and we at our clinics don’t give up on either.

I’ll end by thanking you for your time and attention.

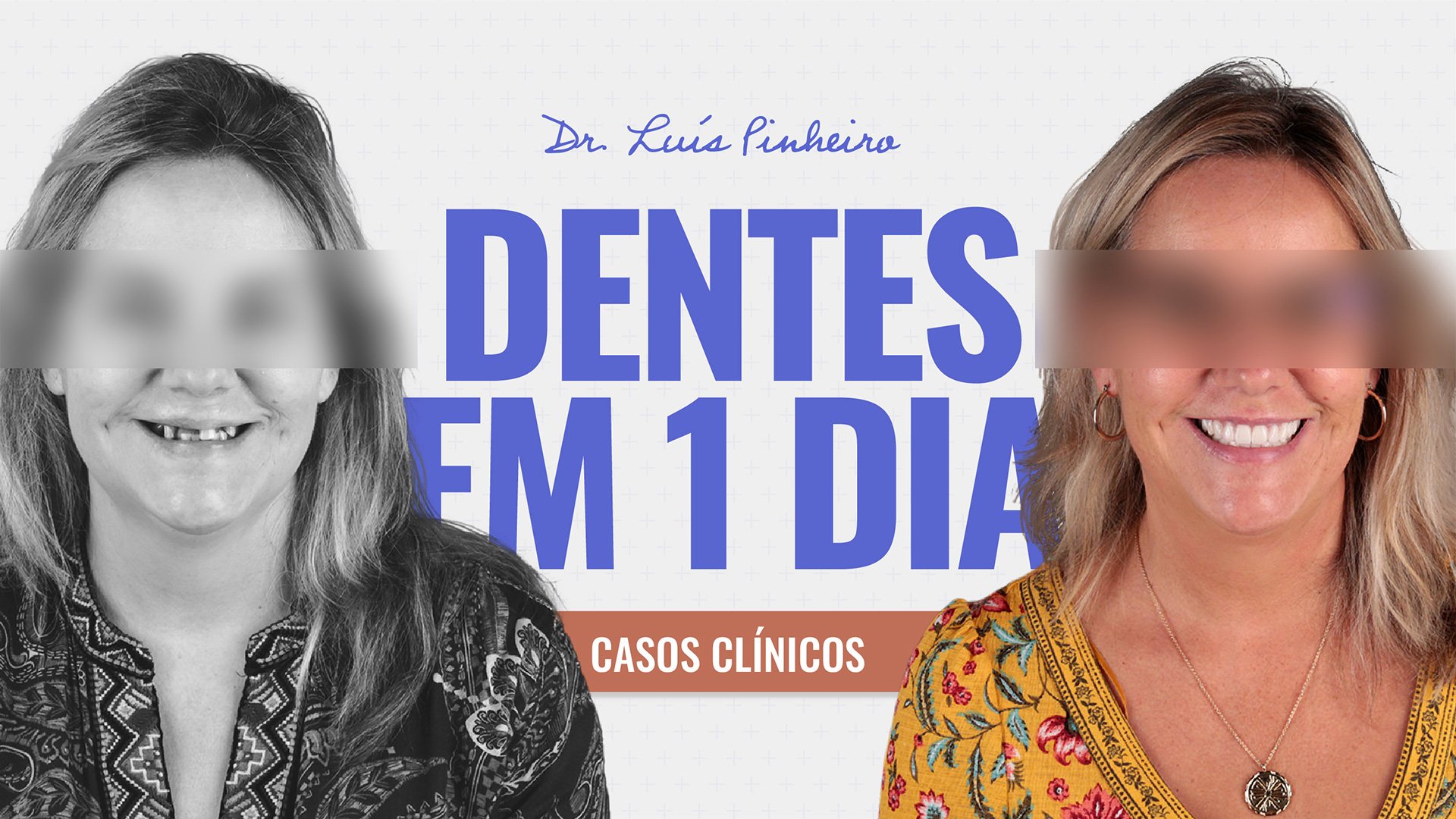

See you soon and don’t forget to be happy. After all, smiling doesn’t hurt.

If it does, if smiling causes you pain, nausea or imbalance, consult your dentist.

Until next time!